By Nanor Froundjian

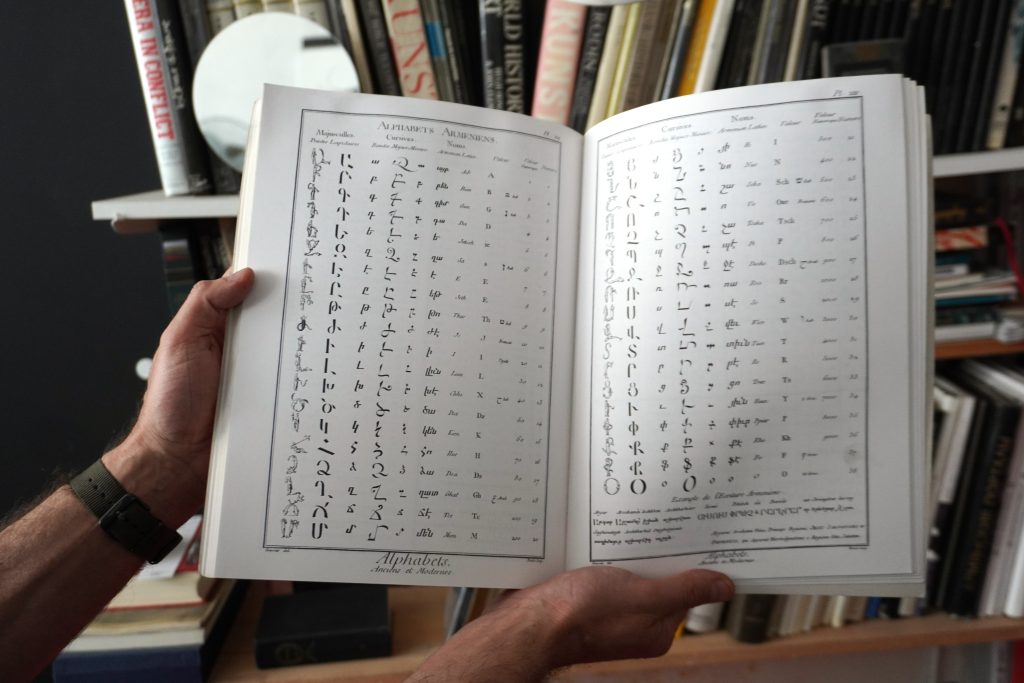

Leafing through the pages of the infamous 18th century ‘Encyclopédie,’ part of which broaches world alphabets, Ruben Malayan recalls seeing the Armenian alphabet’s first letter, ayb (Ա), in a whole new light. It’s a moment he describes as pure illumination.

“The treatment of ayb in that (book) shocked me, because I’d never seen ayb this beautiful – and unusual for me – because I’m used to the ayb they taught us in school,” said Malayan, remembering the moment that inspired a life-changing study of Armenian calligraphy, about 15 years ago.

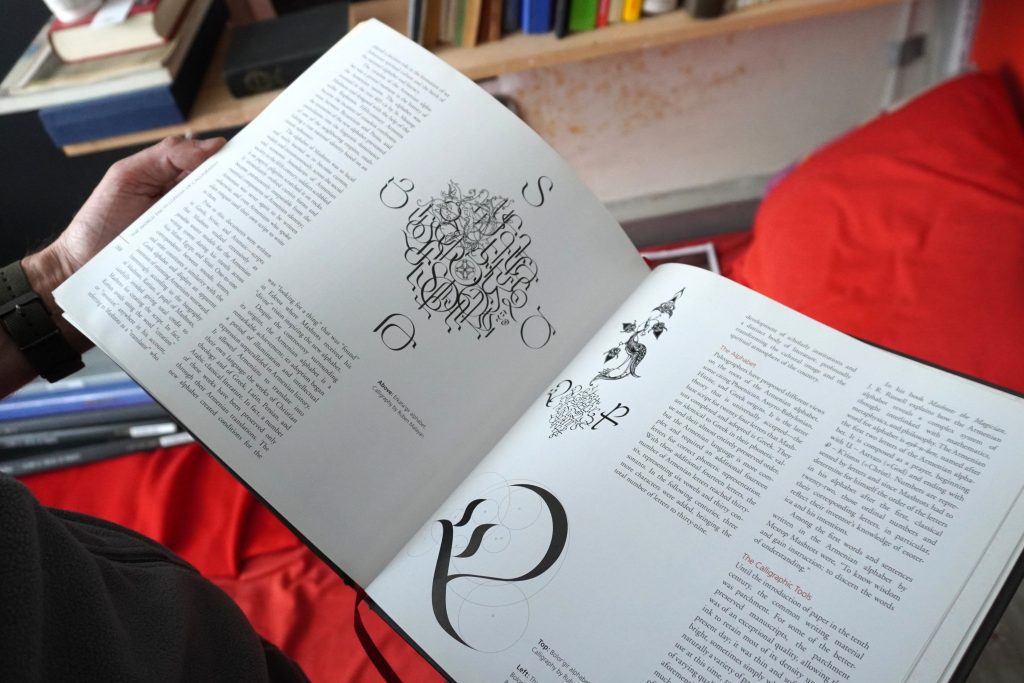

The multi-disciplinary visual artist has since committed to mastering the craft. His work has been featured in publications, including The World Encyclopedia of Calligraphy, Print Lovers Magazine, EVNMAG, Alphabet, and more.

Malayan’s flagship project is a book titled ‘Armenian Letter Culture & Calligraphy,’ a gargantuan undertaking of a comprehensive documentation on the subject, which is in final stages of production.

At the same time, he’s working on a handwritten compilation of calligraphic renditions of Grigor Narekatsi’s poems from the Book of Lamentations.

Still in progress, his work is propped up on an easel by the desk in his workshop, a quaint space with postered walls, complete with a personal repertoire of stacked books, among which lies the ‘Encyclopédie, ou dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers.’

The Armenian alphabet, depicted in different script styles, took up a two-page spread in the French publication whereas most from other cultures were laid out on a single page.

“That was like this magical moment when I realized that I discovered a piece of culture, my own culture, that I had no idea about,” Malayan added on his fascination with calligraphy.

The standard of handwriting, however, has declined over generations, with its flawless execution depreciating in value and no longer commanding the same level of reverence, save niche circles of experts and enthusiasts.

In 2010, when Malayan stumbled upon an elementary school in Yerevan, he asked permission to sit in a class and observe how children learned to write. It confirmed what he’d already known. “I felt there is a lot of room for improvement,” he said.

In his judgement, the benchmark was set below what would inspire a solid proficiency of the practice. The material for students to copy in handwriting were what he characterized as primitive, skeleton letters.

Hripsime Arakelyan, an elementary school teacher at Abovyan School No.7, has also noticed a shift regarding the value of handwriting.

“There’s very little importance placed on handwriting now,” said Arakelyan, who has been teaching students aged six to ten for the past 12 years.

Both Malayan and Arakelyan acknowledge that the overall approach to the significance of the practice in both academia and society continues to dwindle.

She explained that it’s a skill that’s no longer required, even among high-ranking officials and professionals, and therefore has lost its influence – something she largely attributes to an over-reliance on tech.

This shift in attitude is seen among teachers as well, who, like Arakelyan, believe that efforts to fight for the preservation of handwriting would be in vain, since typewriting has become the standard communication method.

“It’s a very laborious task,” she added, explaining that it requires tremendous effort on the teachers’ behalf to ensure that students write beautifully with classrooms averaging 35 children, each of whom would need individual feedback over a 45-minute period.

“There comes a time where we tell ourselves, ‘Well, why are we torturing ourselves over this if this century doesn’t require it from the children?’”

She says teaching methods have changed drastically for the new generation. “The teacher’s word was the rule of law for us. Our parents had to look over our homework and be impressed with our writing,” she said.

Today, she says children must be given an incentive to put effort into their handwriting with a small prize or reward without which they wouldn’t find the motivation to apply themselves.

She believes that in academia, handwriting doesn’t bear any significance. “Aside from forming the student’s character, it doesn’t have any use now. Working on perfecting handwriting is a waste of time for us now.”

It’s a phenomenon observed across the globe, with scores of research studying the erosion of handwriting and its subsequent consequences on mental and physical health alike.

Indeed, a recent UK-based study showed that students are experiencing difficulty holding a pen, raising alarms about the loss of fine motor skills along with its cognitive and social implications.

Similarly in the United States, a 2024 survey revealed that 77 percent of preK-3 educators noticed their students having greater difficulty handling pencils, pens, and scissors compared to students the same age five years ago.

Though elementary school students in Armenia still use pen and paper for classwork, a significant shift towards digital writing tools in and outside of schools has shown what’s at risk.

“Individuality is one of the first things that’s suffering when you are removing handwriting as a practice and moving to a digital form,” said Malayan.

It’s a practice that helps cultivate discipline, commitment, persistence and focus, Malayan explained, all of which he believes develop into foundational life skills.

Artistry and execution aside, he added that writing is not all about perfection; the true merit is something more nuanced than that.

“What actually makes your work valuable, is not the pure technique. It’s the aesthetic framework that you work within.” In his case, a knowledge of poetry, study of mythology and love of architecture provide that foundation.

This resonates with Arakelyan, who’s noticed a clear correlation between personality and handwriting styles.

“Handwriting comes from the soul; it sets in order a person’s movements, thoughts, words. If you pay attention to a child’s handwriting, you can tell what kind of character they have,” she said.

The changes she has seen from one generation to the next show that the appreciation of handwriting and calligraphy has faded, and with it the recognition of its cultural representation.

“It’s a very beautiful language, it encapsulates coarseness just as it does delicacy, and struggle. It’s the essence of our nation,” said Arakelyan.

The post The disappearing art of Armenian handwriting appeared first on CIVILNET.