By Alexander Pracht

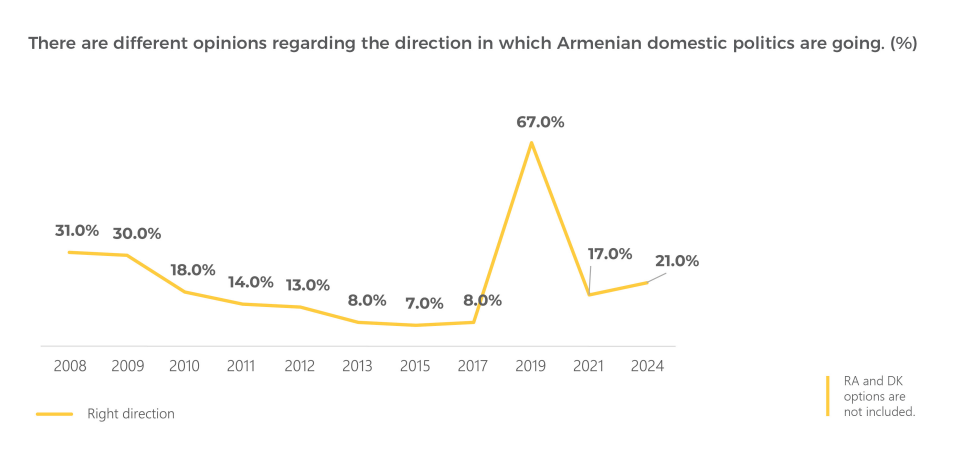

Armenia is a country that experienced a dramatic surge in political engagement during and immediately after the 2018 Velvet Revolution, when massive crowds took to the streets to demand the resignation of then-President Serzh Sargsyan. For a brief moment, it seemed as though the entire population was united in shaping the country’s political future.

However, since then, public participation in politics has steadily declined. This trend is often attributed to growing disillusionment with Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan’s government. Many Armenians feel that the post-revolution leadership has failed to deliver on key promises, including deeper democratic reforms, stronger integration with the West, and, most crucially, the protection of Nagorno-Karabakh.

Domestic politics

In recent years, surveys have consistently shown a growing share of the population expressing dissatisfaction with all political parties and an increasing reluctance to vote at all. For a young democracy like Armenia, this disengagement is compounded by longstanding challenges such as limited political literacy and the relatively shallow reach of civil society.

The most recent research to prove these trends was the nationwide household survey conducted by the Caucasus Research Resource Center (CRRC) in both rural and urban areas of Armenia, involving over 1,500 respondents between July and October last year. The results reveal a major void in the country’s electorate, with 54.7% of respondents saying there is no political party or movement they feel close to, up from 42.8% in the previous Caucasus Barometer, conducted in 2021.

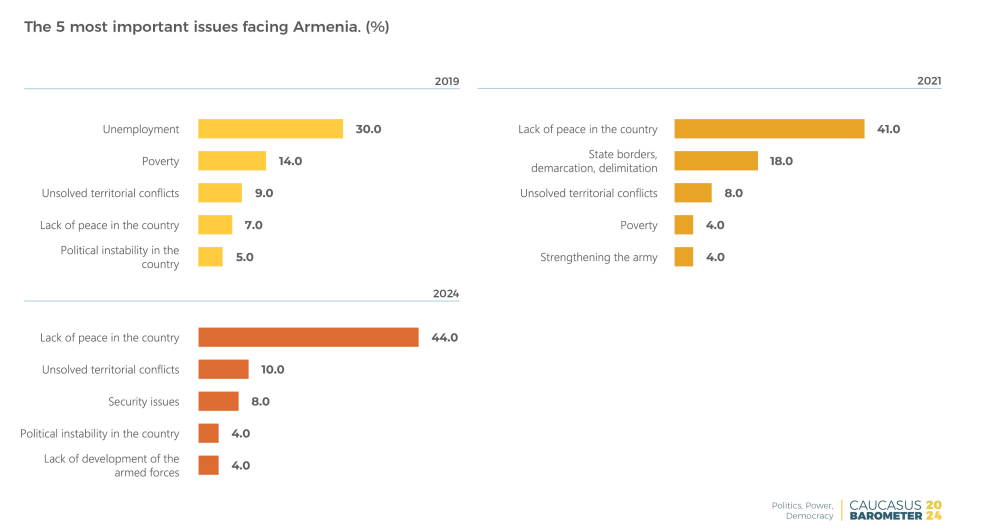

At the same time, over 60% of respondents express interest in domestic politics, and 45% follow international affairs. However, this attention is increasingly centred around national security and territorial disputes, which have overshadowed economic concerns in the public discourse. This shift reflects the geopolitical anxieties facing the country, but it also narrows the space for more structural debates around governance and reform.

“This high percentage of respondents following the news seems surprising given that perceived barriers to democratic participation remain at similar levels to 2021, which is quite low. The jump in the percentage of people who feel unrepresented by any political party highlights the same trend,” Maksim Novokreshchenov, a PhD researcher at the School of Social and Political Science at the University of Edinburgh in Scotland told CivilNet.

The feeling that “people like me have no real influence” is widespread, which is common across many contemporary democracies, Novokreshchenov argued. Combined with the strong nostalgia for a paternalistic state with over 70% believing the government should care for its citizens “like a parent”, it creates fertile ground for populist rhetoric, he believes.

Foreign policy

When it comes to Armenia’s foreign policy, however, there appears to be a contradiction with the trend of political apathy seen in domestic affairs. Although many Armenians seem disengaged from internal political processes, survey data suggests a growing attentiveness to the country’s international alignments.

The 2024 poll revealed a steady decline in the number of respondents who said they were indifferent to Armenia’s membership in intergovernmental organizations, whether existing alliances like the Eurasian Economic Union and the Collective Security Treaty Organization, or potential ones such as the European Union or NATO.

On NATO membership, there is growth on both ends of the spectrum: more strong supporters (17.3% vs 13.1% in 2021), and more strong opponents (26.8% vs 18.7%). The number of undecided respondents has dropped. A similar, though less pronounced, pattern can be seen with regard to European Union membership: 20.9% of Armenians fully support it, up from 15.6%, while 19.8% don’t support it at all, compared to 12.3% in 2021.

Such an engagement is most likely due to the recent Eurovote initiative, organized by non-parliamentary forces last year. The petition to launch Armenia’s EU membership track gained more than 60 thousand signatures and was approved by the country’s National Assembly in February. Discussions around the potential membership likely increased popular interest with the issue.

“This does not point to an ongoing full-scale political polarisation, but these seem to be the lines across which it may form in the future,” Novokreshchenov said. “What seems interesting in this context is the growing consensus about Armenia’s relationship with the Eurasian Economic Union, where public opinion seems to be shifting more uniformly in a negative direction. What partnerships and unions the opponents of EU and NATO integration are going to seek in this situation is an interesting question.”

How social trust affects political engagement

Social trust and interpersonal connections are essential pillars for building a well-functioning civil society. Mutual support and a sense of unity, even if not in political views, then at least in basic existential matters, are crucial for sustaining a healthy political environment. In societies where trust among individuals is strong, people are more likely to cooperate, organize, and engage collectively in civic life. Conversely, a lack of social cohesion can lead to fragmentation, isolation, and apathy, undermining efforts to cultivate democratic institutions and participatory governance.

The survey results demonstrate complex and sometimes contradictory social sentiments. On one hand, there is clearly a high level of social cohesion: 63.7% of respondents report having plenty of people they can rely on in times of trouble. This suggests strong personal networks and a sense of solidarity at the interpersonal level.

“Yet this sense of interpersonal trust doesn’t seem to extend to society at large. Generalised social trust (to the other people overall), which is critical for the functioning of civil society and economic cooperation, remains relatively low. This disjunction between personal and societal trust is not unique to Armenia; in fact, it is a common situation in post-Soviet states, but it can have far-reaching implications for both democratic engagement and market stability,” Novokreshchenov told CivilNet.

He also pointed out that there is an acute perception of injustice among Armenians, with more than half of the population feeling they are treated unfairly by the state, and around 70% believing that Armenia’s courts favour certain citizens over others. “This deep mistrust in the judicial system can reinforce feelings of exclusion from democratic processes,” he concluded.

Engage and organize

Armenia faces formidable external and geopolitical obstacles, from the ever-present threat of renewed war with Azerbaijan, to closed borders with two neighbors, persistent pressure from Russia, and the internal crises shaking many Western democracies that once served as models. Yet one of the most urgent and underestimated challenges lies within: the growing political apathy of Armenia’s own citizens.

A disengaged society, reluctant to contribute to the development of democratic institutions, risks stalling any progress achieved in recent years. Regardless of individual views toward the current government, meaningful democratization cannot originate from government offices alone: it requires active participation from below. A “third force” will not emerge spontaneously; it is going to be built by citizens who choose to engage and organize. Without that grassroots energy, Armenia’s democratic future remains uncertain.

The post Armenians follow politics but reject political parties, survey shows appeared first on CIVILNET.