At the beginning of the 20th century, different peoples living in the Ottoman Empire were trying to find an answer to the question – Can Turkey be reformed? Armenians, Greeks, Jews, Albanians, Kurds, and of course, Turks.

The empire, which had a remarkably long life of about 600 years, was experiencing a significant decline, heading towards collapse, and the question of whether a common vision for the future could be created in the midst of the ensuing chaos occupied the minds of an entire generation of intellectuals. The efforts of Ottoman opposition figures to work together against the regime of Sultan Abdulhamid were a result of this search. The Sultan had continued the modernization steps initiated by his grandfather, Mahmud II, but turned it into a bloody authoritarian regime. This is partial explanation for the enthusiastic reception of the 1908 Constitutional Revolution by all ethnic and religious groups living in the empire, which promised freedom, justice, and equality.

Since then, more than 110 years have passed. Isn’t it a strange twist of history that the same question is now being asked for the Republic of Turkey, which was established as the continuation of the Ottomans?

However, all propositions that the Ottoman state could be reformed and saved from disintegration were proven wrong. The Adana Massacre that followed just a year after 1908, the Balkan Wars a few years later, the Armenian Genocide in 1915, and the Ottoman Empire’s disastrous defeat in the first World War, which it had entered with the ambition of territorial gains – together, they brought an end to the empire.

The Republic of Turkey, which was established in its place, is now preparing to celebrate its 101st anniversary. But this celebration is overshadowed by political, social, and economic crises. These crises are largely caused by the return of issues that the Ottomans couldn’t resolve, postponed, or swept under the rug, coming back to haunt like ghosts. It’s impossible not to recall Marx’s famous statement, referencing Hegel: “History repeats itself, first as tragedy, then as farce.” There are many lessons to be drawn from these historical repetitions, and in this article, I’ll try to find an answer to the issue from the perspective of today’s Turkey, setting aside the tragedy-farce dichotomy.

First, a situational analysis. Turkey has been governed by Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s party, the AKP, since 2003. Since 2013, there has been a shift toward a one-party and, later, a one-man regime. Initially defeating the military, distancing the army from politics, making numerous reforms as part of the goal of EU membership, launching the Kurdish peace process, and seemingly attempting to address the injustices faced by minority communities, including Armenians, Erdoğan gradually began to toughen his stance in order to hold on to power, relying on the politics of polarization by exacerbating tensions such as secular vs. religious, Turkish vs. Kurdish, and Alevi vs. Sunni. Particularly after the failed coup attempt in 2016, Erdoğan used this as an opportunity to consolidate his power and, following the 2017 constitutional referendum, he established an undemocratic system calling it the “Turkish-style presidential system,” becoming the indisputable “President” of ultra-nationalist and Islamist factions, governing the country from the palace to which he withdrew. (Speaking of palaces and withdrawal, it’s impossible not to think of Sultan Abdulhamid, whom Erdoğan admires a lot.)

Today’s Turkey has turned into a cumbersome one-man party-state structure. In the past, the undemocratic state established behind the name of the founding leader, Atatürk, was the source of many problems, but Erdoğan’s AKP, which came to power with the aim of democratizing it, has brought Turkey back to an even more regressive point than before. Those who hoped that time would bring progress, advancement, and freedom have been deeply disappointed. The political stage built on tension, violence, repression, and marginalization condemns the people of Turkey to increasingly worse living conditions.

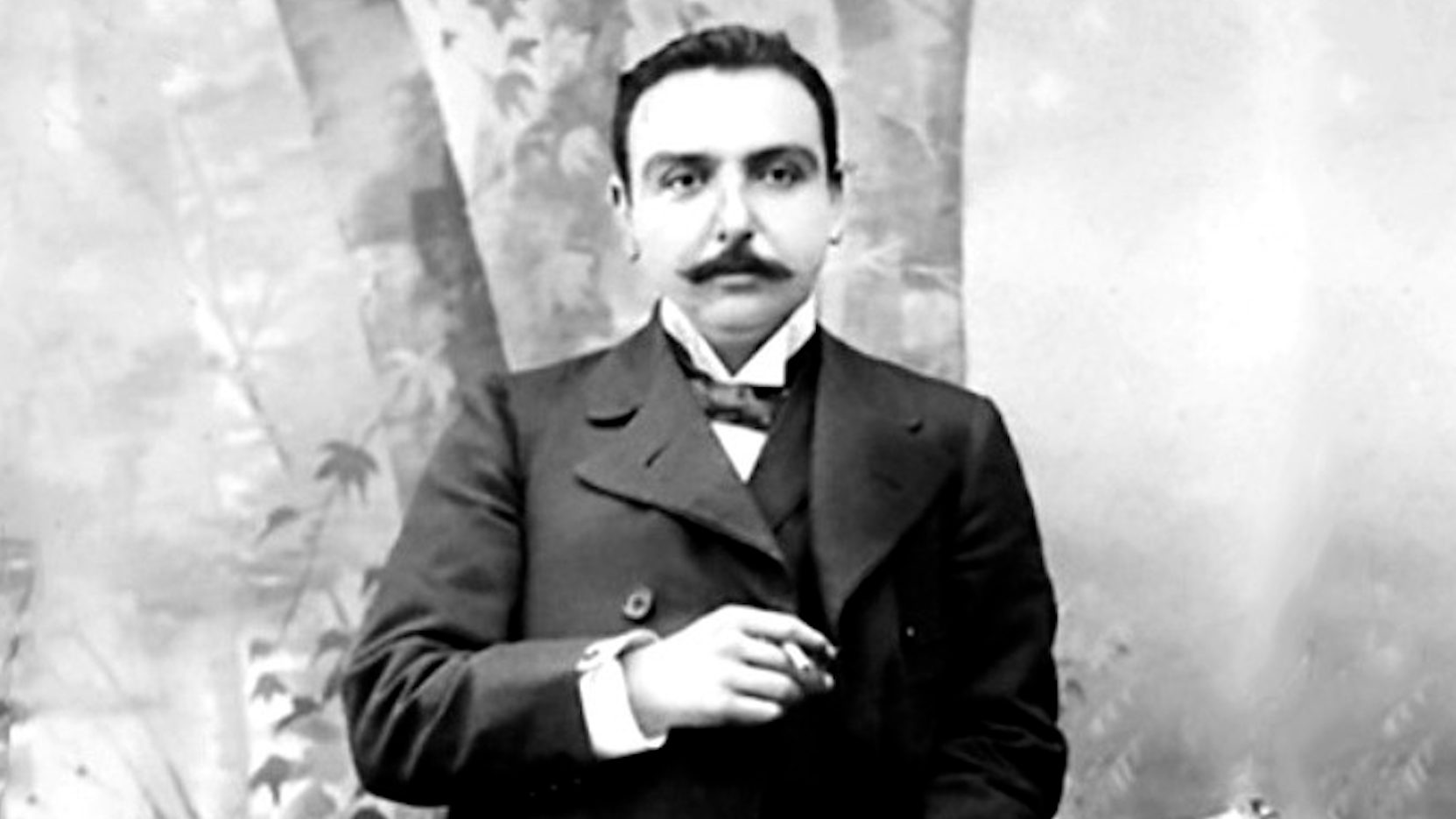

In such circumstances, I recall the Armenian political activism, revolutionaries, and reformers of the years around 1908. Krikor Zohrab, one of the most well-known among them, was a great figure in Armenian literature, as well as being a journalist and a lawyer. He worked for the end of Abdulhamid’s tyranny, was targeted by the regime and had to go into exile, but returned to Istanbul after the 1908 Constitution was proclaimed and was elected as a deputy to Ottoman parliament for three terms. He was one of the most influential figures of the time. Zohrab’s vision was to live in peace in an Ottoman Empire where decentralization, parliamentarism, democracy, and equal rights for all peoples prevailed. All his efforts in Parliament and behind the political curtains were to ensure that these principles were embraced by broader segments of the society. In this respect, calling Zohrab the “Last Ottoman” is quite realistic. However, his pacifism, Ottomanism, and sense of justice didn’t prevent him from becoming one of the victims of the Armenian Genocide. The Ottomans killed the Last Ottoman with their own hands.

Clik here to view.

A century later, at the beginning of the 21st century, another figure who shone in Istanbul is often identified with Zohrab. Like Zohrab, journalist Hrant Dink fought for the establishment of democracy, human rights, and equality in Turkey. He advocated for Turkey to confront its past crimes against humanity, thus building a more humane future for itself. Through his newspaper, Agos, he tried to explain the problems faced by Armenians to non-Armenians. He tirelessly worked for Turkey to achieve a system and social structure that met European standards as a respectable democracy. He believed that the path to healing the Turks’ social pathologies lay in confronting their own past, and that a respectful approach to the pain of the people they lived alongside was essential for Turkish-Armenian reconciling. However, like Krikor Zohrab, Hrant Dink was targeted by Turkish nationalists and was assassinated. If Zohrab was the Last Ottoman, then Dink was perhaps the “First Free Citizen” who deserved to live in the imagined democratic Republic of Turkey. The Turks killed that first free citizen with their own hands as well.

Clik here to view.

From this perspective, the answers to the question of whether Turkey can be reformed seem quite bleak and depressing. The older generations of non-Muslim minorities in Turkey always gave a negative answer to this question, drawing from their life experiences: “No, this is Turkey, it will never change, nothing will get better.” My generation, which came of age in the late 1990s and 2000s, thought that those times were over, that the country was opening up through public debate, that society was transforming, and that this transformation would eventually change the state, too. We often smirked at the cynicism of the older generations, thinking they were afraid and that we were brave. But time has led the country not to a better place but to a worse one, and this has been a heavy and painful defeat for us. Few defeats can be as heavy as realizing that the previous generation was right.

So, what’s the answer to the question? Can Turkey be reformed, can it move in a positive direction? Honestly, I don’t know either. If you had asked me ten years ago, I would have said yes, of course. Today, I have fewer hairs, and my beard has white strands that weren’t there back then. And believing in the truth of philosopher Antonio Gramsci’s famous formula, I always try to be guided by the pessimism of the intellect and the optimism of the will. I believe that the next few years for Turkey, especially in terms of the early election I foresee in 2026 or 2027 and what happens afterward, are very critical. The candidate that the opposition will field against Erdoğan, the political line that person will adopt, and whether a more democratic or more authoritarian path will be taken, particularly regarding the Kurdish Issue and other major problems, will show us whether there is still hope for Turkey. Or Not. I am 47 years old today, and I hope that when I have passed fifty, I won’t be one of those saying, “No, this is Turkey, it is anti-democratic and oppressive, this will never change.”

—

Clik here to view.

Rober Koptaş is a writer and publisher, lives in Istanbul. He served as the editor-in-chief of Agos newspaper from 2010 to 2015 and the general director of Aras Publishing from 2015 to 2023.

The post Can Turkey Be Reformed? appeared first on CIVILNET.