About four months ago, I wrote an article for Civilnet and explained how events of a scale that might not happen in other countries for months, maybe years, take place within a few days in Turkey, just as if it’s an ordinary occurrence.

The three incidents I mentioned happened within three days: Anti-immigrant violence that started in the central city of Kayseri and spread to many other cities, and the nationalist frenzy within the country triggered by the Turkish national football player Melih Demiral making a racist Grey Wolf sign during the European Football Championship.

Those were the first two. The third was the threat of closure faced by Acik (Open) Radio, a radio station known for its emphasis on pluralism, due to a statement regarding the Armenian Genocide. In this news-addicted country, the first two events have already been forgotten, but Acik Radio couldn’t escape the plan drawn for it and was officially shut down. Thus, for the first time in Turkey, a media outlet was closed because it mentioned the Armenian Genocide. Being First doesn’t always mean progress, does it?

Taking a closer look at the Acik Radio “saga” provides quite concrete information about today’s Turkey. Everything started with a broadcast on April 24, 2024, Armenian Genocide Remembrance Day. As they had done every weekday morning for years, the station’s founder Ömer Madra and his co-host Özdes Özbay were discussing current events with their guest, one of Turkey’s leading liberal intellectuals, Cengiz Aktar. The Istanbul Governorship had banned Armenian Genocide remembrance events, even though they had, for nearly a decade, been held publicly. This was the first example of the pressure the local representative of the Erdoğan administration was bringing on this matter. Cengiz Aktar brought up this issue, reminded the audience of the significance of the day, and with his words, commemorated the Armenian Genocide, noting that the regional governor had not allowed commemorations this year. The conversation continued along these lines. However, the complaint made to CİMER, the system created by the Erdoğan regime that functions as a complaint mechanism for citizens and often as a denunciation hotline in political matters, it was claimed that Acik Radio was engaging in “Armenian Genocide propaganda.” The accusation was serious.

Then, a third institution, the Radio and Television Supreme Council (RTÜK), which had been established years ago to suppress the media in Turkey, stepped in. RTÜK outwardly appears to be a civilian institution comprised of representatives from parties with parliamentary seats, but its structure heavily favors the ruling party and its allies, ensuring that every media-related decision desired by the Erdoğan regime passes through it. When the CİMER complaint was forwarded to RTÜK, the institution acted as a censorship mechanism, imposing a five-day broadcast suspension on Acik Radio and a fine of 190,000 TL (approximately $5,600). These penalties both financially strain alternative media outlets with limited resources and, at the same time, marginalize them by distancing them from their audience, making it difficult for them to attract new advertisers.

However, due to a system failure, the penalty imposed on Acik Radio was overlooked. Unaware of the penalty, the Acik Radio management continued its broadcasts. From RTÜK’s bureaucratic perspective, this meant that Acik Radio was defying and challenging the decision. The consequence of this was license revocation. Could there be a better opportunity to silence a dissenting broadcaster? Even though Acik Radio realized the situation and paid the fine, it could not escape closure. Thus, after broadcasting for 30 years, a special media outlet, which was an important part of the media pluralism process in Turkey during the 1990s, cherished by its listeners for its quality broadcasts was shut down. I was not just one of those loyal listeners but also a programmer, presenting the Radio Agos program during my years as Agos editor-in-chief.

On October 16, the day the decision was implemented and Acik Radio made its final broadcast, hundreds of people gathered in front of the radio building, sad but determined to stand by their radio. Ironically, Acik Radio was neighbors with the Depo Art Center, founded by Osman Kavala, the businessman and philanthropist unjustly imprisoned for the last seven years. Another “coincidence” is that Kavala, too, was determined to confront the Turks’ responsibility for the Armenian Genocide.

Together with their listeners, the management of Acik Radio is determined to defend their rights through legal means and to reclaim their license. If the efforts fail, the possibility of continuing with a new radio channel might be a possibility. After all, Turkey is a country where similar censorship has been applied for decades and the resistance to this kind of repressive steps vary. For example, before and after the genocide, when the Armenian newspaper Azadamard (Battle for Freedom) was shut down, it was replaced by Artaramard (Just Battle), and when Artaramard was closed, it was succeeded by Cagadamard (Battle at the Front). In the Republican era, when the satirical magazine Marko Pasha, published by the great Turkish humorist Aziz Nesin, was shut down, it was followed by Merhumpasha (Deceased Pasha), Malumpaşa (Well Known Pasha), Hür (Free) Marko Pasha, and then Bizim (Our) Pasha.

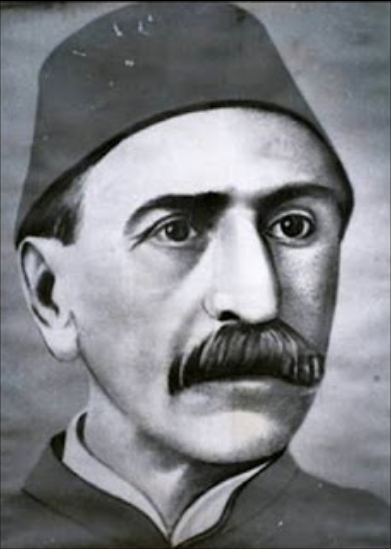

The real and beloved Marko Pasha, Marko Apostolidis.

Marko Pasha was not a fictional character, but a real historical figure. His real name was Marko Apostolidis (1824-1888). He was a Greek doctor loved by Ottoman citizens from various ethnic backgrounds. He founded the Red Crescent organization, rose to the membership of the Senate, and became so famous for taking time to listen to people’s troubles and seeking solutions that the phrase “Go tell your troubles to Marko Pasha” became widespread. In the 1940’s, author Aziz Nesin, with his sharp wit, named his magazine Marko Pasha to highlight the people’s problems despite the indifference of the ruling class. Today, neither Marko Pasha himself, nor Aziz Nesin, nor his magazine exist. But Turkey’s problems are still piled up like mountains, with Acik Radio’s closure added to the mound. For now, all I have is the opportunity to write and record these injustices in history — at least as long as we can still write in Turkey – albeit it involves taking certain risks… Who knows, maybe Marko Pasha, now in the Other World, is reading what we write.

Rober Koptaş is a writer and publisher, lives in Istanbul. He served as the editor-in-chief of Agos newspaper from 2010 to 2015 and the general director of Aras Publishing from 2015 to 2023.

The post “Go Tell Your Troubles to Marko Pasha” appeared first on CIVILNET.