By Brigitta Davidjants

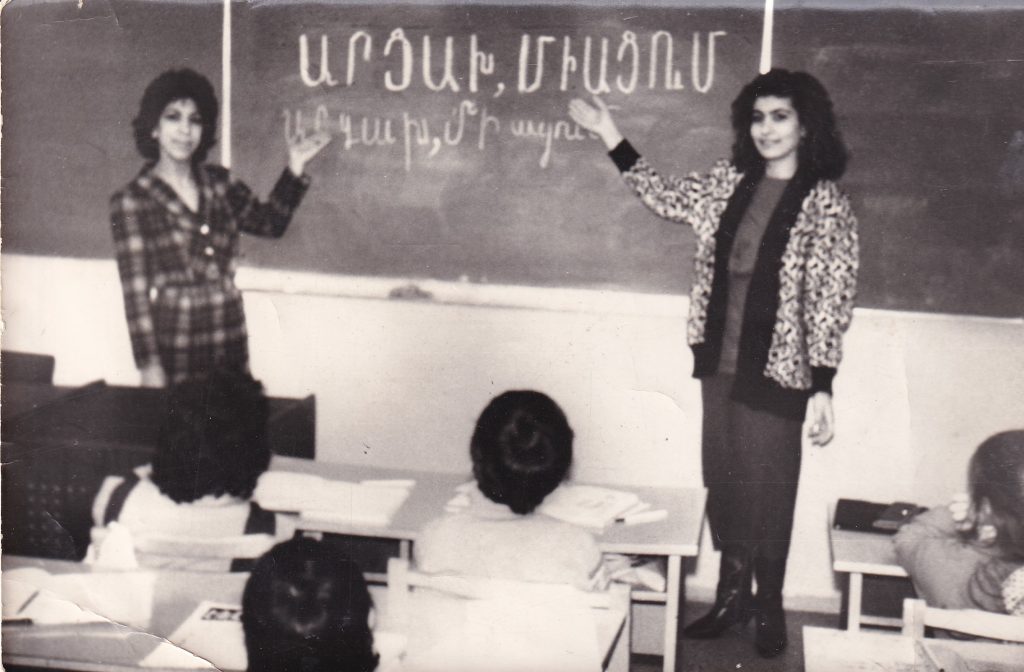

I never told my parents I didn’t want to attend Armenian Sunday school. Hence, I spent all my Sundays at Tallinn Pedagogical University, where our Armenian classes took place, and where teachers Armine, Gayane, and Sara tried vainly to instil Armenian language in us. To be honest, during all those years, from 1987 to 1995, I only learned the Armenian alphabet and how to sing Mozart’s “Spring Song” in Armenian.

It took me many years to realize how much effort our parents had put into my tedious childhood. But at one point, I became curious and asked myself what motivated my parents to go through all this. As a result, I ended up researching the birth of the Armenian community in Tallinn. I interviewed eight Tallinn Armenians, both women and men, who were key figures in establishing the Armenian cultural community in Estonia’s capital. Simultaneously, a community was formed in Tartu, in southern Estonia.

Arrival in Estonia

It is not precisely known when Armenians first arrived in Estonia, but by the first half of the 19th century, at least a few hundred were undoubtedly there. Many arrived from the Russian Empire’s territories, following Khachatur Abovyan’s footsteps to the University of Tartu. There, they published a newspaper, had a library and a literary circle, and actively participated in the political life of the future Armenia. The Bolshevik Revolution of 1917 likely marked the end of this migration.

The number of Armenians in Estonia gradually increased in the 1960s and 1970s. Most were assigned by the Soviet labour system to various industries; others came to study or marry, mostly Estonians or local Russians. And then, in the 1980s, came perestroika, the political and economic reforms initiated by Soviet leader Gorbachev. Estonians greeted the changes with excitement but also suspicion, as the promises of the Soviet authorities had often remained unfulfilled. In the Soviet Union, there was no possibility of creating an ethnicity-based organization of migrants. Still, in the late 1980s, with the national awakening of Estonians, new opportunities arose for all.

The first step by Armenians was taken in 1987 with a newspaper advertisement in Sovetskaya Estonia by my father, Artem Davidjants. He was looking for Armenians interested in starting an Armenian Sunday School (the same one I so badly tried to avoid) with language courses for kids.

“We were sitting in the kitchen with Karen and Sofia when we read in the newspaper that Armenian language courses for children were starting. We decided to go and see what was going on,” one Estonian-Armenian community member reflects.

Some people were also approached directly by Artem; for example, painter Aragats, who had his atelier in Tallinn’s old town. “Once Artem came to my studio. He asked for my opinion on that matter. In a few minutes, we already liked each other very much. So, after a few days, I went to this meeting,” says Aragats.

At first, four to five families responded to the advertisement. Later, as the information spread, roughly a hundred people attended the Armenian National Cultural Society constituent assembly in April 1988.

The question arose about registering such an association because of the need for a legal basis. Eventually, the Armenian Society became a collective member of the Estonian Heritage Society. That was one of the first anti-Soviet organizations “in disguise” in Soviet Estonia, as one of its aims was to achieve the country’s independence. In public, the aim was to preserve Estonian heritage, both material and intellectual.

Motivations for establishing the society

The birth of the Armenian community in Tallinn is often related to the first Karabakh war and perestroika. However, this was not entirely true, although patriotic sentiments certainly influenced Estonian Armenians.

“We came together because we wanted to preserve our national identity, especially our language and culture. And we knew about the diaspora. Even during the Soviet era, there was no Armenian who hadn’t heard of the Armenian communities and their great figures, starting with Nubar Pasha and ending with Calouste Gulbenkian,” Artem recalls.

Interestingly, many of the earliest Armenian activists in Estonia were from Baku – probably many of them were spurred on by a similar experience of being in a foreign community, even if, officially, there were no diasporas in the Soviet Union.

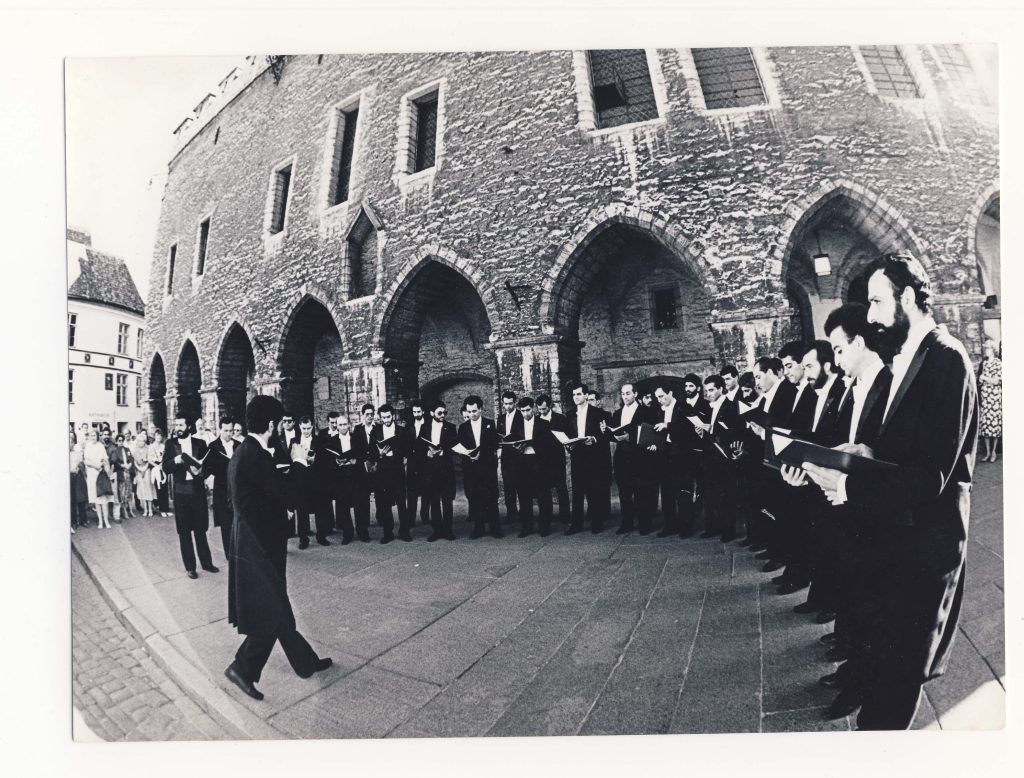

In the late 1980s, the Armenian Society in Estonia thrived with vibrant concerts and exhibitions, and the newspaper was published regularly. The 1990s, however, were a relatively dark era for everyone. Many lost their jobs, the state had to be rebuilt from scratch, and commodity capitalism reigned. Yet, the Armenian cultural community continued to exist.

Christianity, Language, and Genocide

The most important aspect that people wove their identity around was the language, which many did not know, especially those from Baku. Thus, the first impulse for creating the association was the need to organize Armenian language courses. The importance of knowing the mother tongue and passing it on to the next generation of Estonian Armenians was stressed by many.

“There is a saying that a nation must know its language. It is our sin that our children don’t know it. The children whose parents came from Armenia were lucky because their first language was Armenian; our children started with Russian, which wasn’t good,” recounts Sofia who was one of the first who came to the meeting with her kids.

A pivotal event occurred in 1993 when a church community was established, finding its home in Tallinn’s Jaani-Seegi Church. The formation of the Church gave a community new momentum. As in many other Armenian communities, all the people mentioned the Armenian church as an essential anchor in their Armenian identity. On the other hand, with the impact of the Soviet legacy of secularism, many of them emphasized that they were not religious, so the Church was mostly seen as a crucial part of Armenian cultural heritage.

“In 1993, we got the Church. It was in horrible condition, but there was no money for renovation. Our teenagers did it all by themselves. They were all dirty and dusty but did it to save money,” Sofia recalls.

Garik, another community member, sums it up: “An Armenian might be a believer or not, but the church is important.”

To my surprise, the 1915 Armenian Genocide was almost referred to only indirectly, and probably, the difficult period of the 1990s was much more in the minds of many. All the people I interviewed emphasized that Armenians always survive.

As Artem puts it, “Armenians survived the crisis and did everything to return children to their parents’ social status. Now their children belong to the intellectual élite.” However, a certain level of hostility was present while speaking about Armenia’s Muslim neighbours, which was the case especially with male research participants but less with women. Yet, genocide is definitely essential to Estonian Armenians, as it is commemorated every year on April 24.

Defining Homeland

According to diaspora scholars, three parallel visions of Armenia often dominate in the present-day Armenian diaspora. The first is the post-Soviet Republic of Armenia, the second is historical “greater Armenia,” with its splendorous past tracing back to ancient times, and the third is the hometown or village of the ancestors, often located in the territory that Armenians had to leave after genocide in the Ottoman Empire.

However, only some of my respondents were tightly connected to these visions of Armenia. Only Ira stated: “Armenia is my home. I really miss it a lot. My fatherland is there, but my home is here, with my children. I couldn’t even think of leaving them, but I’m still very drawn to Armenia. I raised my children as best as I could. I taught them my language and customs, and they love what they learned.”

In turn, another women expressed an intense longing towards Baku – where she was born and raised, but which was a host land for her predecessors.

The Estonian-Armenian community is also attached to Estonia, probably because it is a democratic country that supports its national minorities, and Armenians appreciate this favourable milieu. They all expressed their close attachment to Estonia and called it their homeland. As Karen said: “I came here when I was 20. Sitting around the table, I say the first toast to Estonians […]. How many of our kids have graduated cum laude from the University of Tartu, though they’ve come from a Russian language environment!”

“I feel that we owe a debt to Estonians [who supported Armenians during the Karabakh conflict and the Spitak earthquake]. Creating our Society was our way of thanking the Estonians,” Garik, another community, member notes.

Finally, over 35 years have passed since the Armenian Sunday School began. Estonia has become a free country, the first graduates have grown up, and many of us now have children of our own. I didn’t learn the language at Sunday School, but at some point, I found myself organizing local cultural events and introducing Armenian culture to Estonians. Probably, the efforts of our parents were not in vain, and their values have been passed down to us, their children.

Brigitta Davidjants is a researcher at the Estonian Academy of Music and Theatre, where she wrote her doctoral thesis on the construction of Armenian national ideologies. She is also a long-time journalist who has published popular science and fiction books and articles. She is currently an intern at Civilnet.

The post Armenians in Tallinn: The Birth of a Community appeared first on CIVILNET.