By Brigitta Davidjants

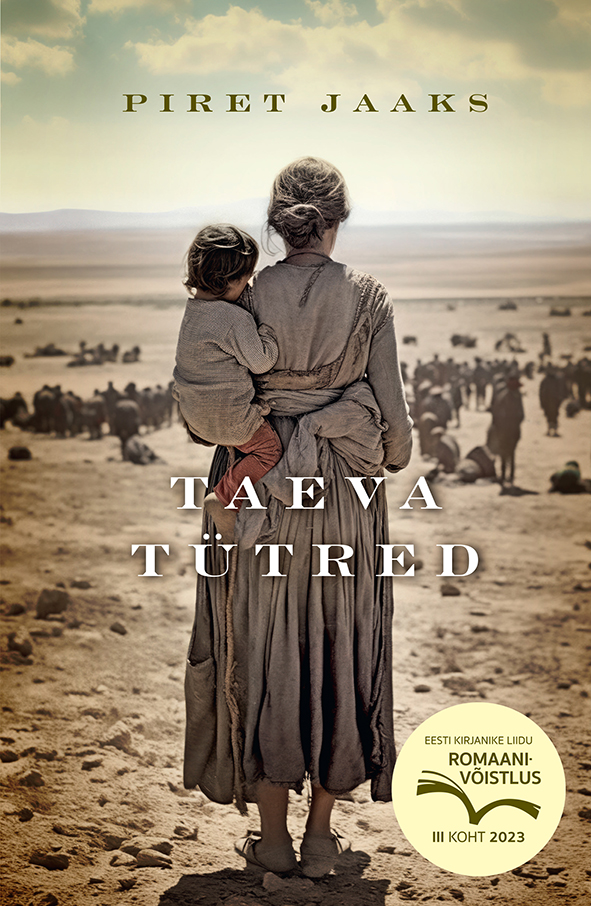

Estonian author Piret Jaaks’ historical novel, ‘Daughters of Heaven’ (‘Taeva tütred’), secured third place in the prestigious 2023 Estonian novel competition. After exceptionally positive reviews, the novel, which depicts the Armenian Genocide through the perspective of Estonian missionary Hedwig Büll, has claimed a prominent spot on the personal rankings of literary critics and has already sold out, prompting a reprint.

Until recently, the name of the Baltic-German-origin Estonian missionary, Hedvig Büll, remained relatively unknown to both Estonians and Armenians. However, Büll’s life resembles an enthralling adventure film. Born at the end of the 19th century, she dedicated her efforts to her work at the missionary orphanage in the Ottoman Empire. When the Armenian genocide unfolded in 1915, she rescued numerous orphans and widows from imminent death. Later, she played a pivotal role in establishing shelters, factories, schools, hospitals, and housing in Syria.

‘I have been connected with Hedvig Büll’s hometown, Haapsalu, where the local museum also has an exhibition about her, for many years. I have lived and worked there, and my grandmother lived there,’ explains the author Piret Jaaks. ‘When I read her story, I immediately realized that it was big, deep, moving, and touching, and definitely worthy of being written down as fiction, though I didn’t start writing it right away. The final push came from the prevailing world situation, another military conflict in which, once again, innocent victims – women and children – were dying in front of everyone’s eyes. This made me realize that it was time for Büll’s story to become a novel because it has so much to teach us today.’

Krista Kaer, editor-in-chief of the Varrak publishing house, adds that Estonian writers are often very Estonian-centric, while ‘Daughters of Heaven’ tells a larger and more international story. She also says that the story teaches us the greatness of being human: ‘The courage to stand up to injustice and the importance of mercy. Hedvig helped many, risking her own life in the process. It is also a lesson in the power of faith, self-reliance, and finding support in difficult times. Hedvig never lost hope; she always believed that salvation was possible and that people could be helped (by God and her). Hedvig’s story is a missionary tale that teaches us how important a drop of water in the ocean can be.’

With the eyes of beholder

Symbolically, the onset of the Armenian genocide is marked on 24 April 1915, when several hundred Armenian intellectuals were rounded up, arrested, and executed in today’s Istanbul. For many Armenians, historical memory revolves around this pivotal event, intertwined with personal stories of ancestors meeting tragic fates in the former Ottoman Empire. The action in Jaaks’ book takes place more on the empire’s periphery, concurrently in Estonia, a bit in the Russian Empire and Germany, and the Ottoman Empire’s city of Marash.

The author traverses unfamiliar landscapes, providing an outsider’s view of the region. The atmosphere is convincing, making it easy for the reader to imagine themselves in a Middle Eastern town at the beginning of the last century, with its vineyards and local Armenian churches. There is even a sense of the mundane, where tragedy arises from the everyday life of ordinary people. Evil comes to people in broad daylight, in the blazing sun.

The novel is remarkable because the author herself is not Armenian. She does not tell the story of her family. While Armenian authors tend to focus on the direct victims of the genocide and their descendants, foreign authors often shift the focus to eyewitnesses who unexpectedly discover themselves as participants. So, there is also a touch of biography in Jaaks’s novel, although the biography is of a Baltic German. So, ‘Daughters of Heaven’ is also a book about trauma, but the focus is on the eyewitness and the ‘secondary trauma’ of witnessing suffering. Even if the novel’s protagonist is not herself a direct target of ethnic cleansing, women are always at risk in a traditionally male environment. So were the missionaries in the crumbling Muslim Ottoman Empire, and this ever-increasing sense of danger around women is convincingly conveyed by Jaaks.

Book launch at the Vabamu Museum in December. The conversation with the author, Piret Jaaks (center), was led by Brigitta Davidjants (left). Passages from the book were read by the actress Maarja Mitt-Pichen (right).

Inspiring also today

Jaaks’s novel is also a profoundly feminist story – of women holding together in the most terrible circumstances. The reader encounters women of different generations and ethnicities with diverse cultural backgrounds and religions, many of whom are united by the realization that domestic life is not necessarily the only path for a woman, to quote one of the characters. The book’s women choose to live as missionaries in a distant war zone rather than conforming to traditional gender roles. In doing so, the book offers a beautiful vision of faith. The author accomplishes this without glorifying institutional faith, prioritizing the personal relationship with God.

This approach has clearly succeeded because the response has been very positive, and the author has received letters from local Armenians and Estonians. “People say it’s historically important to keep Hedvig Bülls legacy of humanitarian actions alive. Several women have said that Hedvig’s story also gives them the courage to follow their chosen path. I have also received several letters from Christians who have thanked me for introducing religion as a personal and philosophical reflection. The fact that Hedvig Büll’s story still touches people shows that her mission and its effects are timeless,’ says Jaaks.

The novel also introduces another kind of mother figure, the protagonist Hedvig Büll, to whom a German living in the Ottoman Empire asks, as if in passing, ‘Are you going to mother Armenian children?’ At the same time, the protagonist’s relationship with her own mother plays an important role. That way, the author creates an imaginary line between biological and situational motherhood, which are not necessarily so different, and blood is not necessarily thicker than water.

Piret Jaaks has systematically approached her material as someone with an academic background. The reader can see on every page that she has carefully studied Büll’s biography, her correspondence, and the historical context of the empires. Jaaks interweaves historical facts, be it about persecuted evangelists in the 19th century or the geography of cities, and delicately places her story in a broader cultural-political context. As a writer, she has breathed life into historical events and facts, even if that life is now unbearably horrific. The ending of ‘Daughters of Heaven’ also gives the reader a glimpse of how Hedvig Büll’s life ended. She died in Germany in 1981, allegedly alone and far from happiness. She had hoped to obtain Soviet citizenship so she could move to Armenia. The authorities refused her this – and she would not have been allowed to go there. Thus, at the end of the work, the author alludes to the injustice done to the woman who saved so many people, making the story doubly tragic.

Brigitta Davidjants is a researcher at the Estonian Academy of Music and Theatre, where she wrote her doctoral thesis on the construction of Armenian national ideologies. She is also a long-time journalist who has published popular science and fiction books and articles. She is currently an intern at Civilnet.

The post Armenian genocide novel wins third place in Estonian novel competition appeared first on CIVILNET.