By Hasmik Hovhanissyan

“The children from the high-rise housing estate in Bremen-Nord know exactly where their families come from: Turkey, Russia, Albania. Only with Karla is everything a little different. She knows that her grandmother came to Germany from Istanbul as a guest worker in the 1960s, and that the family has Armenian roots, but they don’t talk about it. When Karla’s grandmother dies, the name of a woman appears, along with an address in Armenia. Karla manages to persuade her father to go on a trip together – to a homeland that neither of them has ever set foot in.”

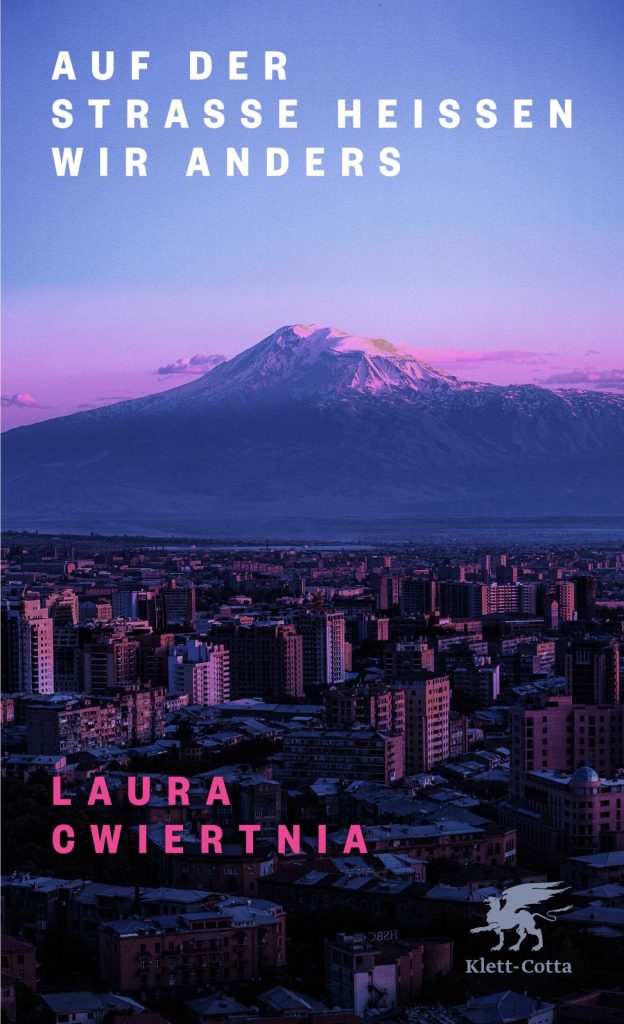

We Have a Different Name on the Street is Laura Cwiertnia’s debut novel. The German author with Armenian roots tells a captivating story about what it means to be a stranger in her own home. Why would one embark on a journey to find her roots? Cwiertnia, whose novel was recently translated to Armenian, sits down with CivilNet’s Hasmik Hovhannisyan to discuss the premise of the book.

“And when I got on the bus a little later, I had the feeling I was looking at my home town in a completely different way. As if the deprived area were not the centre of life here, but merely a silhouette on the horizon.”

Hovhannisyan; This is a good start to an interesting story. Someone embarks on a journey to find a place or a distant relative. But why couldn’t the grandmother tell them about their distant relative earlier? Why did she do that post factum? The story by itself is already full of drama, why add this extra later?

Cwiertnia: Actually, I think it is important to understand that silence is the main topic of the book. It’s not just a trick that I used as if we are in a Netflix movie where we need some drama.

Drama is good. I don’t think that using literature tricks is inherently a bad thing.

I can imagine that there is a huge difference between growing up in Armenia and having the possibility to go to the Genocide Museum, for example. In Armenia, the Genocide is not a silenced topic. The hero of my book, on the other hand, is growing up in Turkey, and later lives in a Turkish community in Germany, where it is not easy to speak about this at all.

Even in Germany?

Yes, and that’s not surprising if you take a closer look at German society. A number of German citizens have a history from Turkey. Their families have Armenian, Kurdish or Turkish roots. When their grandparents moved here in the 1960’s and 70’s, they brought their conflicts, their trauma, their stereotypes with them and often passed it on to the next generation. The inner conflict of the protagonists in my book has a lot to do with the Armenian Genocide and its denial within the society here and there. After the genocide the family faces open discrimination for decades, it faces the pogrom against Christians in Istanbul in 1956. In Turkey, they are forced to hide their Armenian identity. Later, the family moves to Germany where they still don’t feel safe enough to live their identity in public. So the silence of the grandmother is not only a result of a family trauma, but an ongoing fear and even a real danger due to the reality in the post-migrant society.

Eastern Armenia does not appear to be the Armenia that the descendents of Western Armenia are told about. There are those who learned about Armenia from their grandparents, but this semi-European, post-Soviet country is not what they expected to see.

During my public readings, I often say that a Western Armenian going to Eastern Armenia to find his or her roots is almost the same as if a German goes to Switzerland to do that. Yes, there are certain things that you find familiar, but many are totally foreign. At least that is what I felt when I went to Armenia for the first time. In my book the father hopes to discover his homeland in Armenia but then he finds himself in a country that has mountains instead of the Bosporus, a country with a Soviet past and people that speak in a dialect he hardly understands. For him this is a real identity problem, as there is no country where he feels at home. Not Turkey, not Germany, not Armenia. But tell me, how do you feel about diaspora Armenians coming to Armenia?

Western Armenians talk about the past, about homeland, roots and patriotism much more than Armenians living here. There are so many layers here: a Soviet layer, a European layer, the eastern layer.

I would understand if Eastern Armenians sometimes got offended if those from the diaspora came and claimed “this is my home country.” If they put their expectations on a country that has its own culture and society. This is why in my book there is this one character from Yerevan who is called Tigran. His first reaction to the protagonists is, “Another Armenian family looking for their past.” Tigran would prefer normal tourists who are simply interested in that country.

I also think Western Armenians are more romantic than Eastern Armenians and sometimes when they try to interfere in politics or give advice, some tensions arise. It’s all about grasping the meaning of this country. Let’s come back to literature. Do you think that there is more nostalgia in eastern countries? If one wants to write a book where the main character feels nostalgic about his home country, I think one would not choose the Netherlands or Switzerland. It’s always about the East.

Interesting, I have never thought about this. Portugal came to my mind, with its music fado.

The Armenia that you saw. Was it an eastern, or a western country?

For a long time I regarded Armenia as an eastern country, due to its geography and its Soviet past. But then two years ago at the Frankfurt Book Fair I met an Armenian translator who was very strict when saying, “No, we are not an eastern country. We are a European country.” Before that, I didn’t know that there was a debate on that. But of course, I am not the one to decide it.

“Today all you could see through the glass were the empty shop windows. The few shops that still remained in the arcade looked like the last survivors of a natural disaster. I continued to walk across the cobblestones to the harbour, and my gaze lingered on the Weser as it flowed along, always the same green, indifferent to what had been built around it in recent years.”

Tell me about the perception of the motherland in the three different countries you describe – Germany, Armenia, and Turkey. Some people feel that there is a lesser sense of motherland in bigger, more democratic countries that have less social problems. The more problems you have, the more the sense of motherland intensifies. I discussed this topic with another writer, Goran Voynovich, the author of The Fig Tree and Yugoslavia, my fatherland. We came to the same conclusion in the context of post-Yugoslav countries. \

“My father did not want me to talk to others about the fact that he was Armenian. ‘It just causes problems.’”

It’s important to know that we do have many social problems in Germany, although we live in a rich country. People face injustice, conflicts of identity, even poverty. But you are right, in Germany, nationalism is not expressed that much as in other countries. Above all, this is because of our past. Nationalism in our country has led to the worst crime in humanity, the Holocaust. While growing up in Germany, I never said, “This is my great country” or “I love my motherland.” Actually, I would have felt deeply ashamed to do that and the majority of the people I knew felt the same. Today, as we have new extreme right-wing groups getting stronger here, who even glorify the Nazi past, there are even more reasons to be anti- nationalist.

Can’t one be proud of his country without going into extremes?

Personally, I can’t relate to any kind of nationalism as I don’t understand why people always need the differentiation between “us” and “them.” But I wouldn’t condemn anyone who says that he or she loves his or her homeland, especially if that is coming from people that have been marginalized or persecuted. For me it would be much easier to be “proud” of my Armenian roots, than of my German. Because it makes a difference if a population survived a genocide and still fights against a constant danger of being erased – or if a nation has started two world wars and killed six million Jews.

—

Laura Cwiertnia was born in 1987 to an Armenian father and a German mother. She is a Deputy Department Head at Die ZEIT. We Have a Different Name on the Street is her first literary work.

The post We Have a Different Name on the Street appeared first on CIVILNET.